History

How I fell in love with 78 RPM records.

Dick Burns

Dick was a physics major at Yale University, so when it came to all things audio including circuit design and recording he was self-taught.

Dick grew up in New Haven, CT, first entering the world of recording in the early 1940s with a Rek-o-kut record cutting machine that was capable of cutting 78s or 33s. He bought it for personal enjoyment of saving opera broadcasts off the airwaves. AM radio reception was already poor to start with, so each time a car with its old-fashioned ignition system barreled down Shelton Avenue, rapturous singing would get obliterated in a shower of static. He was horrified. He might have gone outdoors at critical moments to deflect traffic. It was that experience that got Dick quite riled and thinking about audio noise reduction.

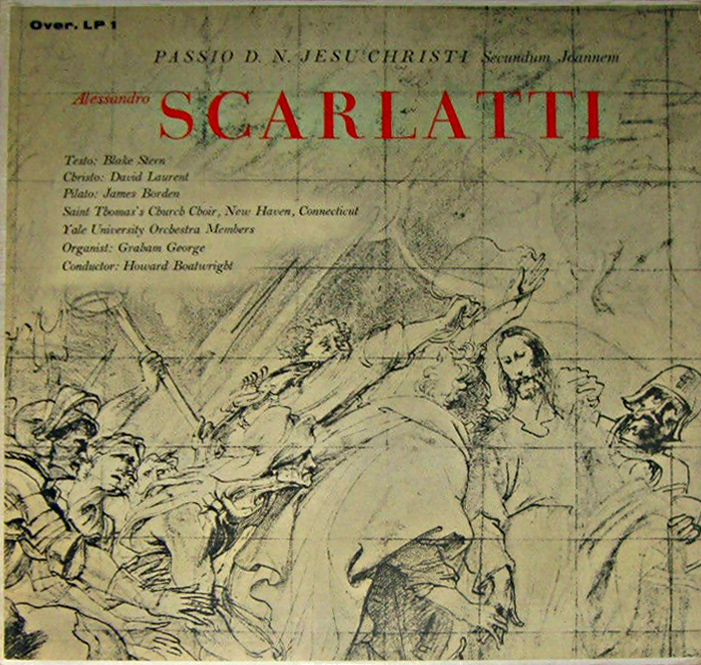

His interest in professional recording was a matter of one thing leading to another. He volunteered to sing in a church choir in New Haven, then was invited to record it. Then Director Howard Boatwright got Dick connected to Yale’s School of Music which opened up important recording opportunities. That appealed to Dick’s entrepreneurial spirit so then he founded a record company, Overtone Records. Dick started to commercialize recordings in 1953.

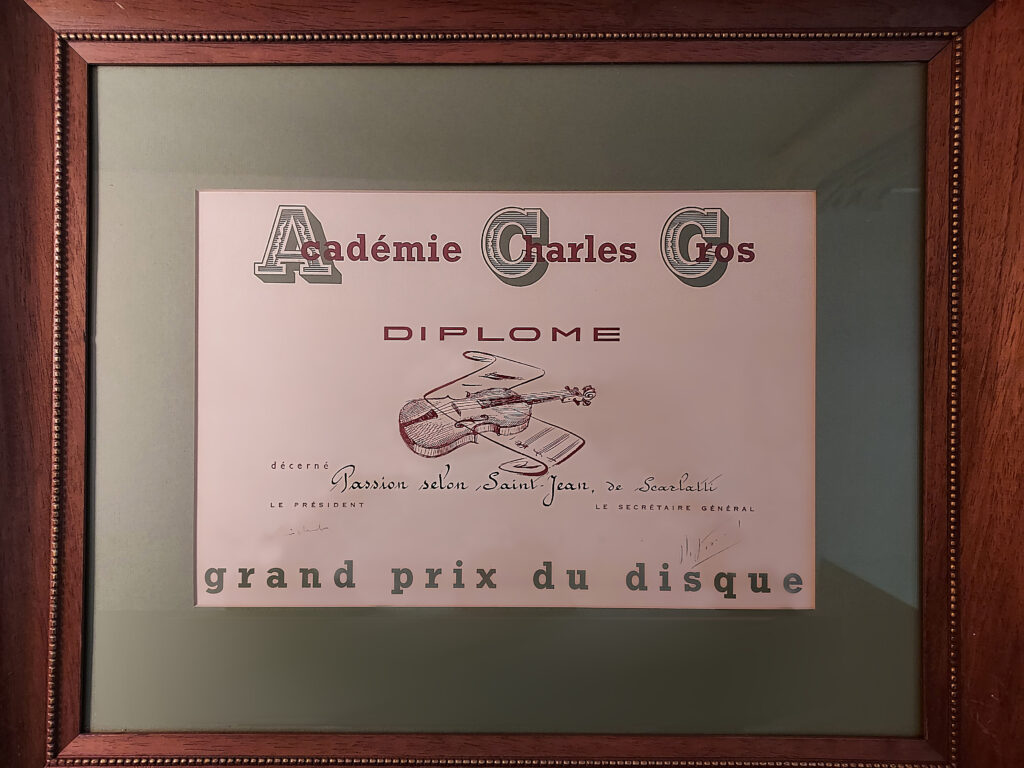

Overtone Records was off to a good start! Dick had designed his own tube-type pre-amps and ten inch reel-to-reel tape recorders and his brother Ted helped him lug the equipment to musical events in and around New Haven. Overtone “1” won a French Grand Prix du Disque!

Of the seventeen vinyl records in the catalog, Overtone 7 “The Songs of Charles Ives” sung by soprano Helen Boatwright was his most famous. By the early 1960s phonograph records were all stereophonic. Since the entire Overtone catalog had been recorded monophonically, sales declined sharply. That actually proved to be good news for Packburn: About the time sales were declining Howard and Helen had taken on new jobs in the music school at Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY. In 1966 Dick accepted their invitation to move to Syracuse to become the school’s recording engineer.

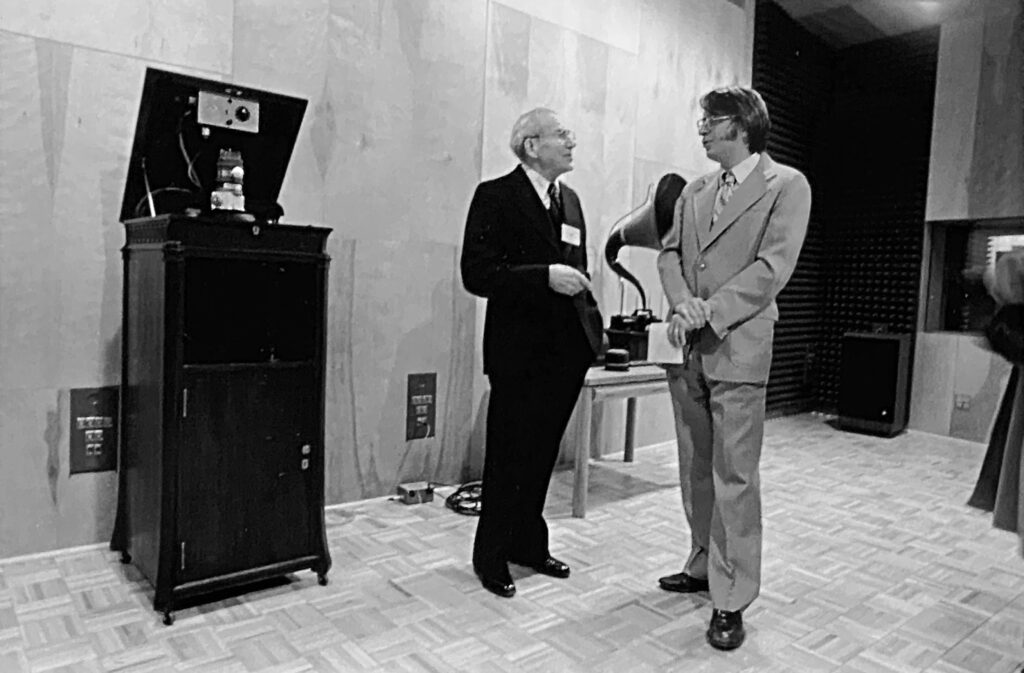

Dick Burns and some of the Overtone equipment in his studio at Syracuse University

Tom Packard

In the meantime I was growing up in Schenectady, NY, still wet behind the ears. Due to the General Electric environment there was never doubt in my mind that I wanted to be an engineer. I liked to tinker in Dad’s workshop.

I was growing up after the era of “vintage records” but clearly remember the tradition of Dad playing his cherished 78 rpm records during and after Saturday morning breakfast. Since I was an impatient kid I remember those times as pure torture. I would watch the needle as the record went around and around until it reached the center groove about 3-1/2 minutes later. The tone arm would click, lift up, and move away. Success! But then Dad would reach into the several disc album set and grab another. That experience would have been the end of music in my life but something snapped inside my brain. Records stopped being torture and became a source of great pleasure. By my high school years I had built a hi-fi system.

I graduated from college in 1968 with an electrical engineering degree and that same year was hired by G.E. in Syracuse. Almost immediately there was a series of improbable happenings. All began with an innocuous question “Is this seat available?” Having not yet own a car I had just boarded the Greyhound bus to Syracuse. Thankfully the answer was “Yes” for the person seated next to me turned out to be the head music librarian at Syracuse University – Don Seibert – someone who was to become a lifelong friend. He had just moved to Syracuse in 1967 and recently met a “Dick Burns” who had also just moved to town. ‘You might want to meet him because he has this massive record collection and one of his favorite composers is the same as yours.’ The next day I phoned Dick. He would be free every other week to play one of his reel-to-reel second or third generation bootleg recordings of the Frederick Delius operas. Not in a million years did I think I would ever hear them. I was in seventh heaven!

General Electric took me away from Syracuse on an assignment for a couple of years. By the time I returned in 1970 I had my first car and bought a grand piano as my very first piece of furniture for the apartment. The piano bench was my sole chair and the piano lid was the dining room table. I did not yet own a bed – a sleeping bag on the floor would suffice. The hi-fi system was located in the kitchen where there was a lot of unused space. I brought my collection of vinyl long play records from home. Things were reasonably stable.

One of those early evenings at Dick’s I asked why he collected 78’s. Their playing time was only 3-1/2 minutes to the side. Since they were both fragile and rare, discs were put on the turntable one by one -a cumbersome process indeed. Further, each disc weighed a pound and to get any decent playing time he had to have thousands. When you climbed the three steps to the front door of his grand 1920s house you immediately were aware that something odd was going on: Over the years, the leaded glass in the eyebrow window above the front door had compressed and bowed outward. When you went upstairs you realized this was due to the weight of the portion of records on the second floor bearing down.

So I had asked Dick ‘why collect 78’s’ and then one evening I answered my own question.

I had brought a copy of Debussy’s Nocturnes on a recently released vinyl LP in stereo that had received rave reviews. After a few minutes Dick interrupted the playing. He was noticeably upset and headed down to grab all the versions of the Nocturnes he had on 78s, brought them up to the attic for playing and proceeded to do so, one after the other. Wow, the performances were all distinct and “heart-felt” but in particular I fell in love with a version conducted by D.E. Inghelbrecht, someone I had never heard of.

From that time onward I was hooked into the world of 78s.

I went around with Dick when he visited local thrift shops and antique stores and since this was in the 1970’s, 78’s were still in common supply because that format had been discontinued by the record companies only fifteen years earlier. People at checkout knew the famous names like Enrico Caruso so for those they asked 20 cents. Dick often preferred the lesser known and much rarer names and would whisper to me “buy that.” It was nice to have my personal advisor. It was also nice that those artists sold for 10 cents. Dick always delighted when he got a bargain.

The album that it got it started.

My 78s were starting to creep along the wall. Out of necessity my second piece of furniture was a five tier record cabinet that I bought at a thrift store. I fastened 1-1/2 inch angle iron beneath each shelf to support the weight. The collection experienced rapid growth, for when Dick went shopping he’d buy something he liked, take it home, keep the better of the two copies, and give me the other – the budding young engineer – for free.

I thoroughly enjoyed playing my records but at the same time realized they were Dick’s discards! Before the notion of Packburn was ever dreamt up I wondered whether I could apply my college training to make them sound as good as his. Maybe it was Dick’s motive all along that those free records would “prime me” for what was to become a business.

The Summer of 1975

That year’s recession hit young General Electric engineers quite hard and I got layed off. That was initially hard on the ego but then I quickly realized that that summer could be an unfettered opportunity to do whatever I wanted! Over the years Dick had familiarized me with audio noise suppressors that he owned that were either brutal to the music or ineffective. We were always bantering ideas. So here was the opportunity handed on a silver platter to knuckle down and invent.

From the start, the focus was on “revealing musical nuance”. Noise reduction was not to destroy those nuances since those were what had drawn us to old records in the first place! What proved challenging for me was Dick having at his disposal 23,000 shellac and vinyl records to choose from. He gathered into several 12 sleeved albums the worst examples of musical transients that needed to be preserved and examples of surface noise to be eliminated if possible.The extremes from this shop of horrors would get played and played again ad nauseam.I would hear clicks and pops in my sleep.

And so that summer I basically took over the laboratory room in Dick’s house. I would build up a design idea on a “perf-board” one after another. After too many circuit modifications the tangle of electronics would become so ridiculous that a fresh board would have to be built from scratch to take its place. .

When a design iteration seemed promising, up to the attic it would go for critical listening on Dick’s home-built Klipshorns. Things seemed to be getting promising. Then suddenly one afternoon came the breakthrough! We played a few of the test records first and then we just had to play something in its entirety. We chose an album of 78 rpm records, Victor set M44, Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben’ (A Hero’s Life). It was now time to build two machines, one for Dick and one for me.

As the year 1975 went on, Dick was visited by a long-time friend Richard Warren, curator of the Yale University record archive. Out of the blue he queried ‘How much would one of those Heldenleben machines cost?’ Wow! The thought of starting a business had never entered our minds..

Company Stories

Going from breadboard of the audio noise suppressor in 1975 to product launch in 1977 was a mad scramble! There were matters of design, documentation, patent submittal and parts purchase. We came up with the company name, Packburn Electronics, and started out as a partnership.

Senior partner Dick Burns had arranged a visit to the offices of High Fidelity Magazine located in Great Barrington, MA. Sound system equipment and phonograph records were loaded in the rear of my burnt-orange 1973 Nova hatchback. As I drove, Dick navigated using his New England fold-out map. We pulled into their parking lot, were greeted, and then ushered into their long-tabled conference room. The room was neat as a pin when we arrived but we quickly transformed it into a laboratory strewn with equipment and cables. For them this was hardly ordinary. Their review which published in August 1977 was titled “A Most Improbable Noise Suppressor” and captured the day thusly: “Dick Burns and Tom Packard constitute the total employment roll and so the whole company had driven to our offices with equipment to demonstrate a Packburn on the spot.” About the demo they wrote: “For closely spaced pops the Packburn produces astonishing improvement – the best (short of ruthless filtering, which of course damages the program) we have ever heard.” News traveled through the musical community. Sales of the then Model 101 started to grow.

.

Our first sale went to Syracuse University where Professor Walter L. Welch had founded the school’s Belfer Audio Archive and Laboratory. It was known for being the largest sound archive at any American university. When I first met Walter in 1977 the archive was located off-campus in a long, poorly lit basement of an old warehouse. Holdings comprised 200,000 historic recordings that included 22,000 Edison cylinders and there was an assortment of vintage playback machines. Fast forward to 1982. Dick and I would be attending the dedication ceremony of a newly constructed building to house the archive, located center-campus and appropriate for the school’s national treasure. Other than the free food I wondered why I had been invited. That was until Walter drew me aside for a minute and shared that their two Packburns, in use since 1977, had prompted a major donation.

.

Our Model 101 in the Belfer recording booth,1977.

Professor Welch and Tom Packard.

There were design improvements to be had so we launched Model 303, our second generation audio noise suppressor. In August 1982 our third generation Model 323 was reviewed in Stereophile Magazine which declared “The KLH TNE-7000A and DNF-1201A (both reviewed in recent issues) are probably, as of now, the Cadillacs of noise-reduction units. The Packburns are the Rolls Royces.” With favorable reviews, advertisements and ongoing word of mouth the market expanded beyond the U.S. to include international record companies, archives and serious collectors. So in 1982 our third generation Model 323 became known as the world supplier in real-time audio cleansing. It was purchased by audio archives, record companies, institutions and serious collectors. About a third of the business became international.

.

Model 323, an early generation model noise suppressor, reviewed by Stereophile Magazine.

Dick Burns did not solicit recording projects outside of his normal work. He knew too well that that would involve a ton of work and between his job at Syracuse University and Packburn there was more than enough to keep him busy! However there were several times he just couldn’t resist.

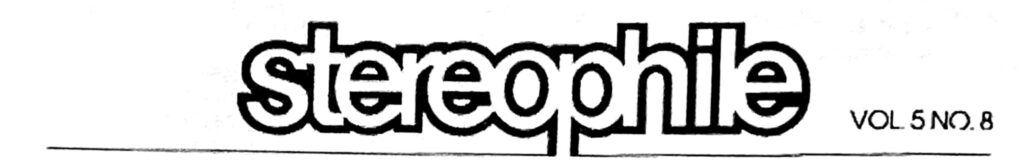

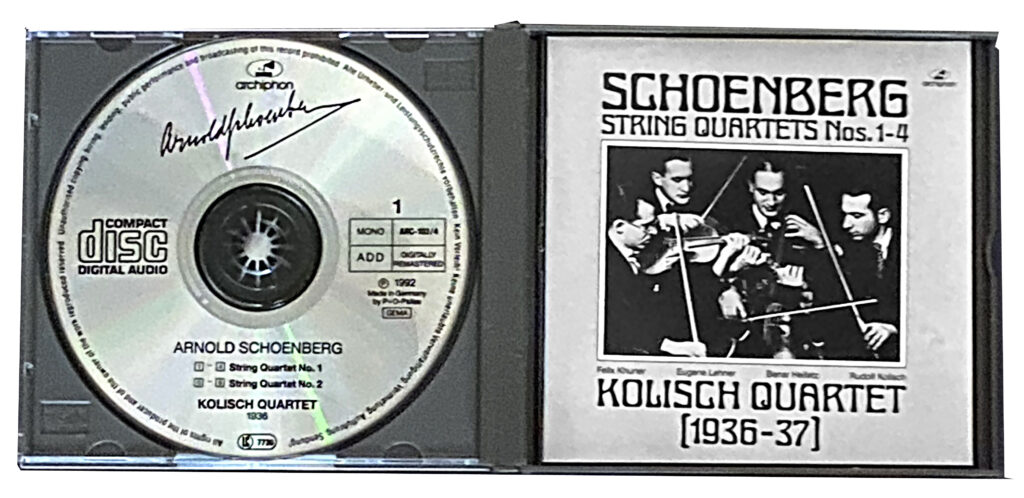

On one occasion – it was a warm and sunny Saturday afternoon in 1985 – our work was interrupted by a knock at the door. Professor Louis Krasner, violin teacher at Syracuse U (check out his biography!) was holding a tightly wrapped brown paper bag between both hands with something mysteriously hidden inside. “Dick, I think you will be interested in this.” Peering inside, there was a group of personally owned white powdering lacquer 78s from the 1930’s! Through all those decades Louis had saved them for the day when technology could do something with them. What made them extrodinary was they were only known copies of the premier peformance of a work he had commissioned. It involved himself as violinist, Alban Berg as composer and Anton Webern as conductor. As predicted, the transfer job would consume many hundreds of hours of labor, gratis of course, a true labor of love. The content and the restorative challenges of the eventually released compact disc received a Gramophone Award.

.

.

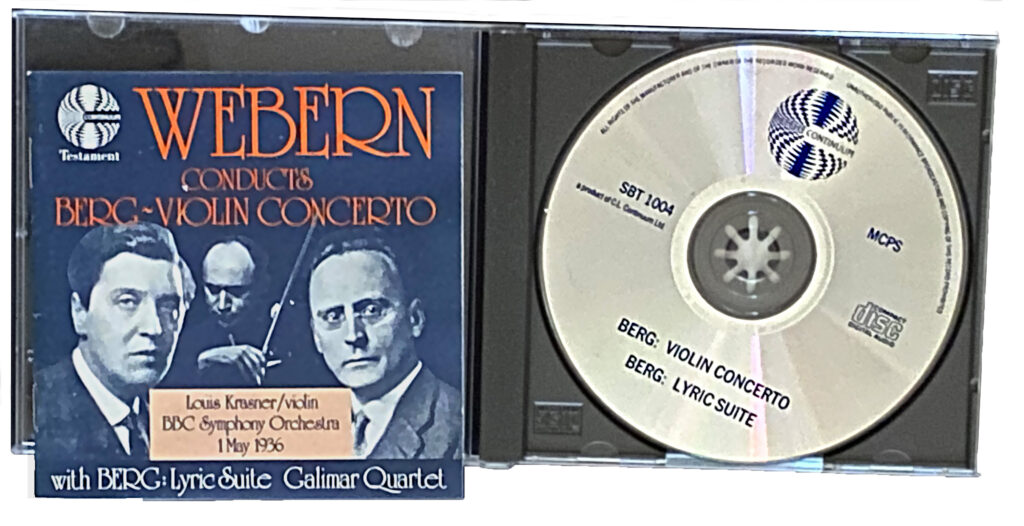

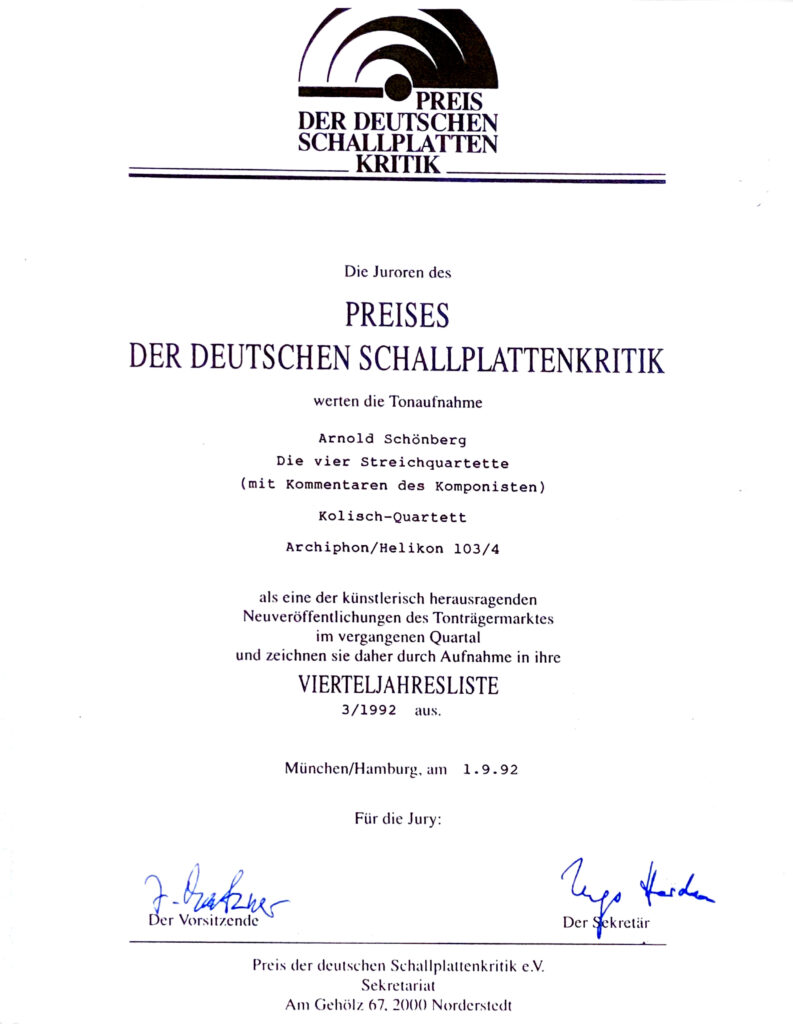

Another project arose from one of the Packburn sales to Germany. This one led to a good friendship between Dick and a Werner Unger. They were two birds of a feather, conversing about this or that until it landed on the Arnold Schoenberg string quartets. Yes, the 78s of them were rare and Dick owned all of them in prestine condition! Dick did the transfer work. The set of compact discs that were released went on to receive the German Record Critics Award.

Dick passed away in 2002 and there is a big empty space, but his dreams through Packburn Electronics would carry on. Afterall there were still friendships to form and refinements to invent. Enter Jim Romano! Our now available fifth generation Packburn – Model 329AD – was eight years in the making. The goals were more consistent noise suppression – both 78’s and 33-1/3 vinyl stereos, easier operation – fewer knobs, improved visual feedback, and affordability. We got there, persistence pays. I use Model 329AD for all my listening. And now it’s available for you!

Our model 325 launched in 2011 is shown above

Our Model 329AD is now available for your listening pleasure!